In May Xi Jinping introduced China’s “dual circulation strategy”. At first this passed without much comment, even from China insiders. However, seasoned China hands are starting to talk about the serious economic implications.

Part of the reason this dual circulation strategy took so long to get attention is its vagueness. The specifics aren’t finalized yet, and are still being discussed internally among top officials in China. The key thing is that China isn’t just sitting back waiting for decoupling to happen. They are leaning into it.

CSIS has called this the “hedged integration” strategy.

The strategy, which envisions a new balance away from global integration (the first circulation) and toward increased domestic reliance (the second circulation), stems from Beijing’s belief that China has entered a new paradigm that combines rising global uncertainty and an increasingly hostile external environment with new opportunities afforded by a floundering and listless United States, which China has long viewed as its most important geopolitical rival.

Even a small change in its mercantilist export strategy would alter global trade and investment flows. In order to better understand the potential impacts, let’s look at each of the two parts.

Balance away from global integration

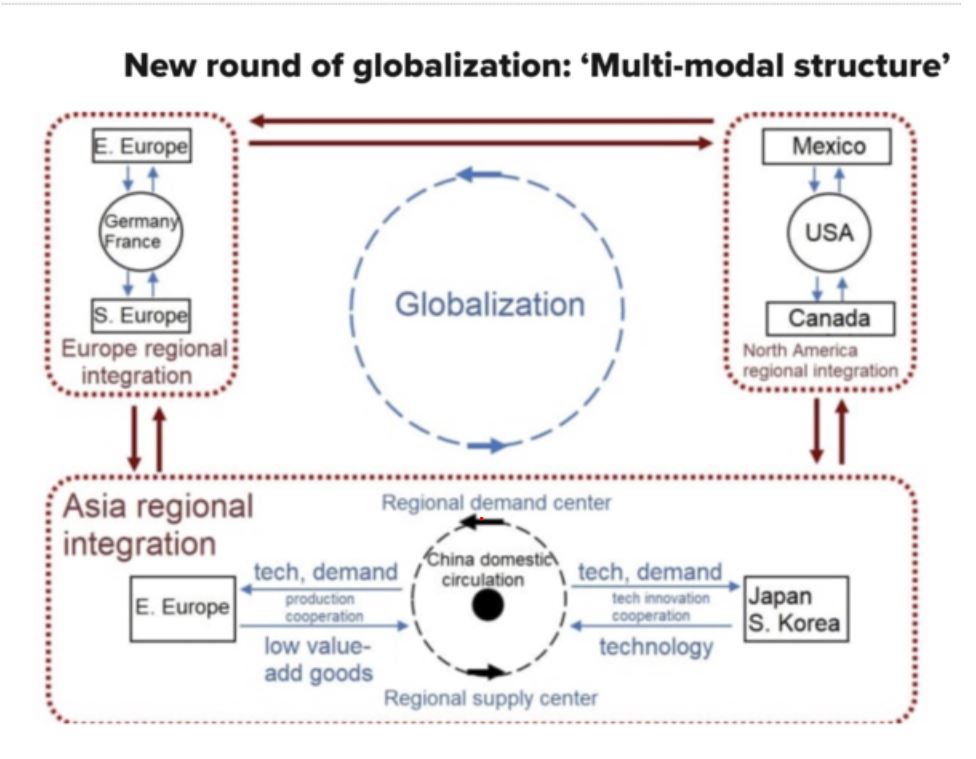

China accepts that supply chains are shifting. Protectionist policies and Covid-19 have both caused companies to rethink their sourcing strategies. More companies will source domestically, or from nearby countries. China needs to become less dependent on western democracies. This is part of the broader trend away from globalization. If this works, China will be less dependent on global macroeconomic cycles.

Increased Domestic Reliance

A stronger domestic economy is necessary to shake off reliance on the global economy.

CSIS describes this part of the program as follows:

As part of the effort to reduce external vulnerabilities, one key element of the DCS is to focus on both the strengths and weaknesses of the domestic economy—consolidating the former and addressing the latter in order to improve economic resilience and self-sufficiency. That means further stoking demand from China’s domestic economy and gearing Chinese producers to meet that demand with expanded output for the domestic market rather than for export—all while finding ways to reduce reliance on external inputs in key areas, including energy, technology, and food.

Do they really mean it this time?

Michael Pettis pointed out that this “new” policy isn’t really new. In 2007 then Premier Wen Jiabao made a speech promising that Beijing would make it a priority to rebalance domestic demand towards consumption.

Of course a lot has changed in the politics of its trading partners since then. It’s possible China will really need to make the changes this time. This Will have profound impacts on domestic politics in China.

Pettis noted in FT Alphaville:

Although the vocabulary has changed, the sustainable growth Chinese policymakers want still requires a major transformation in the way income is distributed to different sectors. Not only is the political challenge as great as ever, but because past Chinese growth has depended so heavily on the current distortions in income distribution, the transformation to a new model will almost certainly require a very difficult adjustment period. For dual circulation to work, internal circulation can only come at the expense of international circulation, and as this happens, wealth – and with it power – must be shifted from today’s elites to ordinary Chinese households.

Check out China Macro Reporter for additional details on China’s dual circulation policy.